Paul Epstein, ND

Sonia Malani

Tolle Causam

Practical Integration of the Mind, Body, and Spirit

Students come to naturopathic medical school with an empty toolkit and a vast amount of curiosity. As students, we aspire to obtain a spectrum of healing principles to take with us after we don our graduation caps and initials that will precede our names. As a 3rd-year naturopathic student with my final year in sight, I have found that staying up-to-date with the latest research and modalities is imperative, as the turnover is rapid. The reality of our changing field asks that we maintain an open mind, knowing that not every patient’s healing journey can be navigated with the knowledge attained in a mere 4+ years; some of the most powerful medicine might be discovered outside the 4 walls of our academic institutions.

Like many of my colleagues, a major focus of mine has been the practical integration of the mind, body, and spirit. A desire to delve deeper into mind-body medicine led me to enroll in the course “Connecting the Cell and the Self: How Biography Becomes Biology,” taught by Dr Paul Epstein, a naturopathic physician specializing in mindfulness and mind-body therapies on the East Coast. This 3-day course explored the idea that “disease tells a story, not just of our cells and our diagnosis, but of our self and our life.”

What I came across in Dr Epstein’s workshop was overwhelming evidence identifying the etiology for many of the chronic illnesses I was seeing in clinic – Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs). As naturopathic doctors, we understand that a diagnosis of IBS-C (constipation-predominant IBS) might be connected to our patient’s stressful childhood in an unpredictable alcoholic household. However, as I transition into the role of “student doctor,” my overarching clinical questions are: 1) how do we address the story of self; and 2) how can we employ the principle of “preventare” when our patient’s biography has already translated into ailing biology? In this article, we follow up on Dr Epstein’s work illustrating the connection between childhood trauma and illness, and use the knowledge gained from his course to begin answering those questions.

Reviewing ACEs

It is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has. (William Osler, MD)

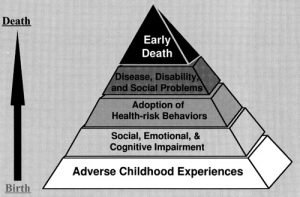

The ACE Study, which was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente and enrolled over 17 000 subjects, found that early childhood experiences correlated with a negative long-term health outcome.1 Ten types of childhood adversity were included in an intake questionnaire: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; emotional and physical neglect; and 5 types of family dysfunction – violent treatment of a mother, mental illness in a parent, parental substance abuse, losing a parent through abandonment or divorce, and imprisonment of a family member.1 When the epidemiology intersected with neurobiology, researchers found that adverse events disrupt normal neurodevelopment, contributing to emotional, cognitive, and social impairment later in life.2 Numerous PET scans of the participants in the ACE study revealed hippocampal and amygdala atrophy, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a hypersensitive amygdala, and impaired orbito-frontal development. The CDC proposed that disturbed neurodevelopment and subsequent social and emotional impairment encourages the adoption of health-risk behaviors and ultimately results in early death (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Life Consequences of ACEs

ACE Pyramid illustrating that ACEs are at the foundation of many of the chronic health conditions and risky health behaviors we encounter in our patients1

Resilience as an Antidote

As a child, the only choice available is to simply survive an experience, to contain the pain and suffering so that life may continue with normality. Healing is a process of developing new relationships to those experiences, learning how to release from the past somatic inscription of childhood trauma.

(Paul Epstein, ND)3

Alongside the ACE study, psychologists and pediatricians in Augusta, ME, began studying the concept of resilience. Resilience is the ability to respond to experiences, fostered by the clinicians, teachers, friends, family, and community in one’s life.4 Researchers noticed that those who scored higher on a questionnaire measuring resilience had a better long-term health outcome. Therefore, if trauma represents one side of the coin, the antidote for trauma is resilience.5

A major indicator of a resilient environment involves 1 or more stable relationships with a primary caregiver.6 In other words, resilience derives from our support system. Adapted in a clinical setting, physicians can use this information to guide their treatment, as resilience can be developed at any age. Dr Epstein utilizes this information to develop a 2-angled treatment plan.

The first part involves modeling resilience for the patient. He uses a therapeutic alliance with his patients to illustrate what a stable relationship and support system could look and feel like. He aims to bring a broader context to resilience, making sure to educate his patients that their relationship with others must be stable, as well as their relationship to themselves. This is where the foundations for health play a role, as proper sleep, drinking plenty of water, eating whole foods, and getting adequate movement and exposure to nature all strengthen a patient’s resilience.

The second part of Dr Epstein’s treatment plan involves guiding the patient through 3 “Living Questions” (listed below). These questions, which the patients ultimately need to ask themselves, help build awareness of their own biography. Only by creating awareness around the experience can we help them to develop a new relationship to the experience. Holding space for the answers that arise out of these questions shifts the consciousness of the patient sitting before us and illuminates their inner healer, or vis medicatrix naturae. This approach is supported by the researchers of the resilience study; ie, they noticed the benefits when “the patients’ own insights about personal motivation on their journey toward health and well-being are both respected and reinforced by their clinicians. This interaction between medical professional and patient does not change the past experiences of the patient; however, it can change their experience moving forward.”5

Living Questions

Question 1: How did I come to be this way?

As mentioned previously, disease tells a story, not just about our cells and a diagnosis, but about our self and our life. This question leads the patient to the truth of what happened to them and the emotions that lie at the core of their authentic being.

Question 2: Am I willing to listen with the ears of my heart to the other voices of myself speaking?

The first question builds awareness; this second question asks the patient whether they are ready to begin this journey of healing. Their willingness (or lack thereof) to listen to their own story can help us identify the obstacles to cure. Is the part of them that’s listening afraid, ashamed, or avoiding their story? How are these emotions holding them back from moving forward?

Question 3: How can I be with my pain of mind, body, and spirit in a way that is wise, compassionate, and healing?

This last question asks the patient to write their own treatment plan by listening to the intelligence of their own body. It is imperative that the practitioner holds space to listen to the patient, as they are listening to themselves. As a new clinician, I often make the mistake of wanting to provide a tangible solution or cure instead of realizing the healing that my therapeutic presence can offer. Dr Epstein reminds us that “in curing, we are trying to get somewhere; we are looking for answers. In curing, our efforts are specifically designed to make something happen. In healing, we live questions instead of answers. We hang out in the unknown. We trust the emergence of whatever will be. We trust the insight will come. The challenge in medicine is not the choice between one and the other; we need both.”

Ask Questions, Hold Space for Answers

To the degree that we do not figure out how to integrate this knowledge into everyday clinical practice, we contribute to the problem by authenticating as biomedical disease that which is actually the somatic inscription of life experience on to the human body and brain. (Vincent Felliti, MD)1

Whether we experience adverse events as a child or adult, we are all susceptible to trauma. What is important is that we are aware of the support we have, both internally and externally. At times of crisis, we need to have someone to lean on, someone with whom to process, and the self-care practices to keep our physical bodies, minds, and hearts healthy and strong. It is important to note that some of our patients with a history of ACEs might require a referral to a therapist further trained in trauma; however, as naturopathic doctors we have the training and capability to address the underlying cause and open the door for healing.

In reflecting on my clinical questions and knowledge gained through this course, to address the story of self, we must be willing to ask the right questions and hold space for any and all answers that arise. In our chronically ill patients, we must move beyond history of present illness and investigate the connection between their biography and their biology. While we can’t control what our patients have experienced before they walk through our door, we can practice “preventare” by strengthening their response to future adversity. Similarly to prophylactically dosing immune support before flu season, we can teach, model, and practice resilient behaviors on a regular basis to increase the host response to adversity in our patients. The Hippocratic Oath reminds us that there is an art to medicine, which can sometimes outweigh a surgeon’s knife, prescription drug, or herbal tincture. Sometimes, the most potent medicine we have to offer is ourselves.

References:

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258.

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174-186.

- Epstein P. Childhood Trauma and Adult Disease: What’s the Real Diagnosis? NDNR. 2013;9(6):1.

- Hobfoll SE, Palmieri PA, Johnson RJ, et al. Trajectories of resilience, resistance, and distress during ongoing terrorism: the case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):138-148.

- Forstadt L, Cooper S, Andrews SM. Changing Medicine and Building Community: Maine’s Adverse Childhood Experiences Momentum. Perm J. 2015;19(2):92-95.

- Key Concepts of Resilience. Center on the Developing Child. Harvard University. Available at: http://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/resilience/. Accessed April 14, 2017.

Sonia Malani, ND Candidate for 2018 and a 3rd-year naturopathic student at Bastyr University, has a keen interest in mind-body medicine. Sonia graduated from New York University with a Bachelors in Psychology. She hopes to pursue further studies in perception and how it plays a role in our healing journey, specifically within the world of oncology. In her free time, she enjoys being both a student and teacher of yoga and meditation.

Sonia Malani, ND Candidate for 2018 and a 3rd-year naturopathic student at Bastyr University, has a keen interest in mind-body medicine. Sonia graduated from New York University with a Bachelors in Psychology. She hopes to pursue further studies in perception and how it plays a role in our healing journey, specifically within the world of oncology. In her free time, she enjoys being both a student and teacher of yoga and meditation. Paul Epstein, ND, is a mind-body therapist, mindfulness meditation teacher, speaker, workshop leader, and author. He graduated from NCNM in 1984. Dr Epstein, who practices in Westport, CT, has successfully advocated for and integrated the clinical application of mind-body medicine, mindful awareness, and contemplative body-centered psychotherapy with naturopathic medicine for over 30 years. He is the author of the book Happiness Through Meditation, has written articles for NDNR, has taught mindful healing workshops, and lectured worldwide at conferences and healing centers. He has also taught at the ND schools, conducts webinars and online training programs, and is an adjunct faculty member of AIHM and IIN. Website: www.drpaulepstein.com

Paul Epstein, ND, is a mind-body therapist, mindfulness meditation teacher, speaker, workshop leader, and author. He graduated from NCNM in 1984. Dr Epstein, who practices in Westport, CT, has successfully advocated for and integrated the clinical application of mind-body medicine, mindful awareness, and contemplative body-centered psychotherapy with naturopathic medicine for over 30 years. He is the author of the book Happiness Through Meditation, has written articles for NDNR, has taught mindful healing workshops, and lectured worldwide at conferences and healing centers. He has also taught at the ND schools, conducts webinars and online training programs, and is an adjunct faculty member of AIHM and IIN. Website: www.drpaulepstein.com